Congratulations! You have all completed your first submission for Unit 10 / Learning Aim A. In this Learning Aim we have looked at the mechanics of film in both macro and micro detail. We saw how narrative and genre are often structured to deliberately appeal to certain audiences, as well as how the meaning of a film is encoded within the cinematography, mise-en-scene, editing and sound.

Now comes the exciting part…

Learning Aim B concerns itself with the pre-production and production of a short fictional film or film extract. You will be placed into groups of three and you will produce material for a fiction film of a specified genre. This learning aim follows on from Learning Aim A in which you analysed films in order to inform your own film production.

In this Learning Aim, you will need to demonstrate that you can manage the filming process and acquire high-quality footage that is fit for a particular purpose (an identified genre or audience). Because you will be working in groups on film making projects, each member will need to be organised so that every member of the group can have an identifiable scene that they have directed or filmed. Care will need to be taken to achieve this without disrupting the overall style of a film (if two scenes are made in hugely contrasting styles, for example) but it is important that every member of the group has an opportunity to demonstrate their ability in this respect.

This Learning Aim begins with an agreed proposal / treatment to turn into a short film. It is important that I manage and approve the films to be put into production carefully to ensure that they can be measured against a particular purpose or genre, are realistic and that they give sufficient opportunities to each member of the group.

Before filming there are a number of pre-production processes which need completing to ensure a smooth production process. These include;

- a detailed proposal / treatment

- screenplay

- storyboard

- production schedule

- location recce

- production budget

What is a Proposal?

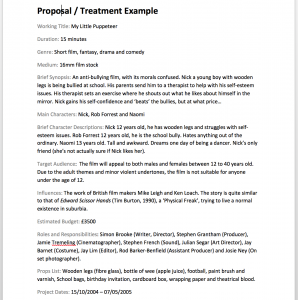

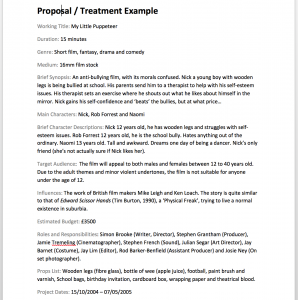

Once your group have decided on a feasible idea you should be ready to produce a detailed proposal. A proposal (or treatment) is a detailed written document designed to obtain approval and support for the project. It should be written in a clear and engaging language that meets the expectations of media producers. It should also be approx. one page long.

A proposal should contain the following; a brief synopsis and rationale for the project (including genre); the structure; main characters; specific information regarding audience; influences; budget and schedule; and key personnel. A completed version looks a bit like this;

You can find a blank template of this document on Godalming Online.

Once you have had your proposal approved you are ready to produce a screenplay and storyboard. You are well tutored in the structure of a film screenplays – on the maxim that each page is approx. 1 minutes of screen time, you should be producing between 4 and 5 pages of correctly formatted script.

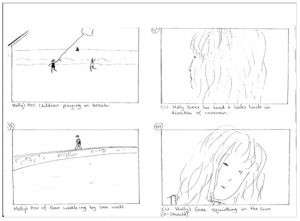

What is a storyboard?

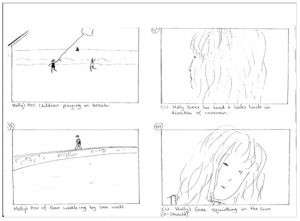

The important part of a storyboard is the story. It is a way of telling your narrative visually, rather like a cartoon strip. Essentially a storyboard tells the story of your film in small hand-drawn pictures. The great thing is you do not have to be a good artist – photographs and stick men drawings are fine.

The importance of a storyboard is to see how all the shots fit together to tell your narrative before you go out and shoot the video. This is like having a visual script.

It is essential that the storyboard frames match the images you want to use in your film frame for frame in sequential order. It is also important that each frame includes essential written technical information for filming. This should include – shot number; camera framing (CU, ExCU, LS etc.); brief description of the shot; an indication of camera movement (zoom, track, etc.) supported by arrows to indicate the direction. Here is an example;

You will find examples and templates for storyboards on Godalming Online.

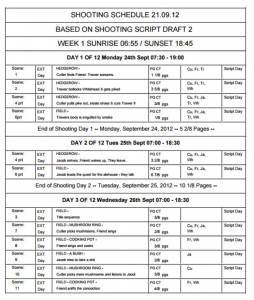

What is a Shooting Schedule?

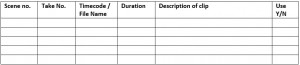

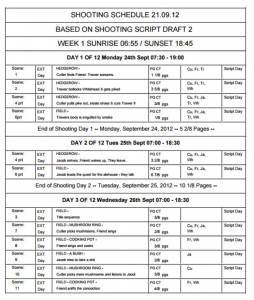

A shooting schedule indicates the total number if days recording that will actually be required to complete the project. Shooting schedule information is assembled to include all major personnel, equipment and locations needed for the entire production. A completed version looks like this;

Again, you can find a template on Godalming Online.

What is a location recce?

A good location recce involves finding suitable locations for each scene and logistically working out what the possible problems would be when filming. It is important that you fully explore the location and provide still images as evidence of suitability, as well as a map and detailed location details. Please use this template (also on Godlaming Online).

What is a detailed production budget?

A production budget indicates all of the costs, regardless of how small, and if unknown, a professional estimate must be made. Please use the template provided.

Diary Blog

As you are producing your pre-production materials and experimenting with production techniques, it is essential that you record your progress on your blog. Keep a daily diary entry of what you have done, what you have learnt and evidence of your decisions and progress.

Good luck folks…I’m looking forward to seeing your creative ideas!

MVP

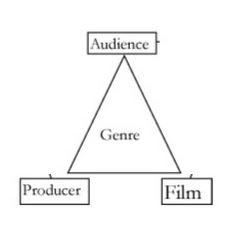

Tom Ryall proposes a theory in which links the film institution, film and audience – suggesting that they are all reliant on each other. The institution produces a film of a certain genre which generates money through audiences buying into the film, and the money generated goes back into the institution to produce more films of that genre. This process will continue until the genre becomes less popular with audiences.

Tom Ryall proposes a theory in which links the film institution, film and audience – suggesting that they are all reliant on each other. The institution produces a film of a certain genre which generates money through audiences buying into the film, and the money generated goes back into the institution to produce more films of that genre. This process will continue until the genre becomes less popular with audiences. A MULTI-STRANDED STRUCTURE means there are several narratives running at the same time. This is very common in television and radio soaps and ongoing drama series, such as Holby City, and The Bill. Robert Altman’s films often employ several narratives which follow a range of characters whose narratives occasionally overlap. His film Short Cuts (1993) follows nine separate narratives over the course of its 3 hour running time!

A MULTI-STRANDED STRUCTURE means there are several narratives running at the same time. This is very common in television and radio soaps and ongoing drama series, such as Holby City, and The Bill. Robert Altman’s films often employ several narratives which follow a range of characters whose narratives occasionally overlap. His film Short Cuts (1993) follows nine separate narratives over the course of its 3 hour running time!